Radical Candor by Kim Scott - Book Summary

This is my summary of ‘Radical Candor’ by Kim Scott. My notes are informal and tailored to my own interests at the time of reading. They mostly contain quotes from the book as well as some of my own thoughts. I enjoyed this book and would recommend you read it yourself (check it out on Amazon).

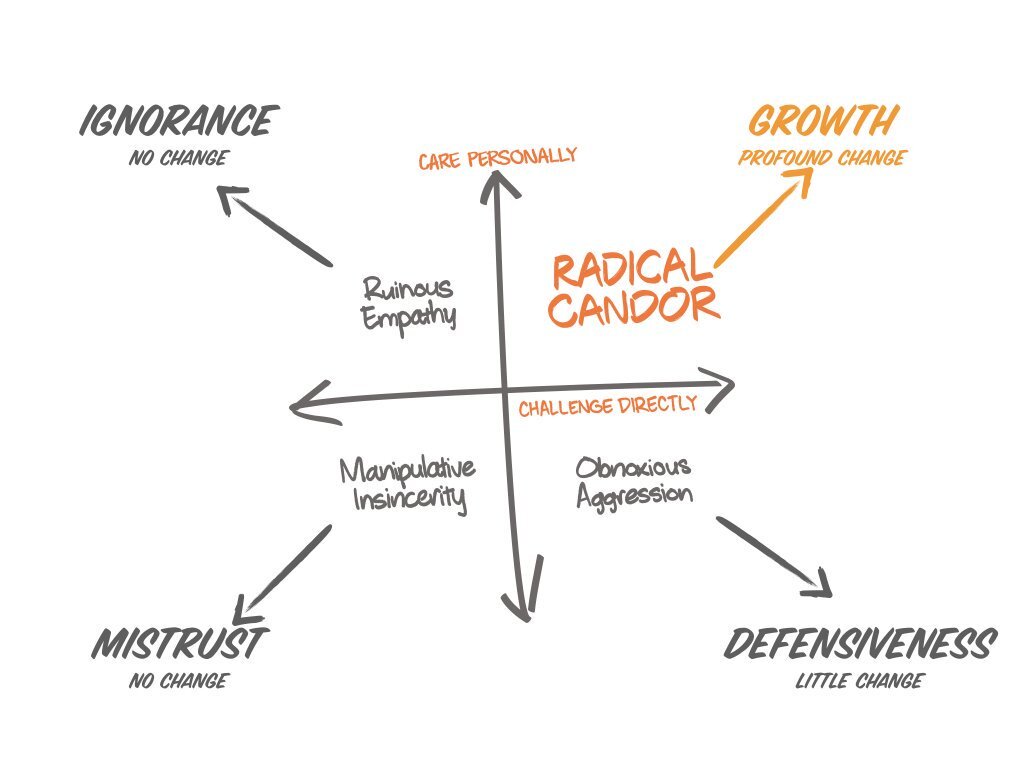

Radical candor visualized:

Principles for giving effective feedback

Avoid manipulative insincerity.

Manipulatively insincere guidance happens when you don’t care enough about a person to challenge directly. People give praise and criticism that is manipulatively insincere when they are too focused on being liked or think they can gain some sort of political advantage by being fake - or when they are just too tired to care or argue any more.

When you are overly worried about how people will perceive you, you’re less willing to say what needs to be said. You may feel it’s because you care about the team, but really, in those all-too-human moments you may care too much about how they feel about you - in other words, about yourself. [note: a reactive leadership pattern, cf. the book ‘mastering leadership’]

“He’ll be happy if I tell him I liked his stupid presentation, and that will make my life easier than explaining why it sucked. In the long run, though, I really need to find someone to replace him.”

Avoid ruinous empathy.

There’s a Russian anecdote about a guy who has to amputate his dog’s tail but loves him so much that he cuts it off an inch each day, rather than all at once. His desire to spare the dog pain and suffering only leads to more pain and suffering.

Most people want to avoid creating tension or discomfort at work. They are like the well-meaning parent who cannot bear to discipline their kids.

Praise in public, criticize in private.

Adapt to an individual’s preferences. While the majority of people do like to be praised in public, for some any kind of public mention is cruel and unusual punishment.

Keep slack time in your calendar to give feedback.

Don’t schedule back-to-back meetings or have twenty-five and fifty-minute meetings with hard stops.

Give feedback in 2-3 minutes between meetings.

Or be willing to be late to your next meeting.

Don’t “save up” feedback for a 1:1 or a performance review.

Don’t let the formal process - the 1:1 meetings, annual or biannual performance reviews, or employee happiness surveys - take over. They are meant to reinforce, not substitute, what we do every day.

It’s best to deliver feedback in person.

You won’t really know if the other person understood what you were saying if you can’t see the reaction.

Most communication is nonverbal.

—

How to share negative feedback

Challenge people directly.

Tell people when their work isn’t good enough. Deliver hard feedback, make hard calls about who does what on a team, and hold a high bar for results. Challenging people is often the best way to show them that you care when you’re the boss.

Challenging others and encouraging them to challenge you helps build trusting relationships because it shows (1) you care enough to point out both the things that aren’t going well and those that are and that (2) you are willing to admit when you’re wrong and that you are committed to fixing mistakes that you or others have made.

“Being responsible sometimes means pissing people off.” - Colin Powell. You have to accept that sometimes people on your team will be mad at you. If nobody is ever mad at you, you probably aren’t challenging your team enough.

Share constructive feedback as early as possible, ideally immediately.

Give feedback as quickly and as informally as possible. It takes discipline - both because of our natural inclination to delay/avoid confrontation and because our days are busy enough as it is.

For every piece of subpar work you accept, for every missed deadline you let slip, you begin to feel resentment, and then anger. You no longer just think the work is bad: you think the person is bad. You start to avoid talking to the person at all.

There are also times when you should wait to praise or criticize somebody. If either you or the other person is hungry, angry, or tired, or for some other reason not in a good frame of mind, it’s better to wait. It’s the exception, not the rule: too often we use the exception as an excuse not to do what we know we should do.

When you say something that hurts, acknowledge the other person’s pain.

Don’t pretend it doesn’t hurt or say it “shouldn’t” hurt - just show that you care.

Eliminate the phrase “don’t take it personally” from your vocabulary. It’s insulting. When you try to soften the blow, you are in effect negating those feelings. It’s like saying, “Don’t be sad,” or “Don’t be mad.”

Instead, offer to fix the problem. Part of your job is to acknowledge and deal with emotional responses, not to dismiss or avoid them.

Only challenge people when it really matters.

Challenging people directly takes real energy - not only form the people you’re challenging but from you as well. Do it only for things that matter. A good rule of thumb for any relationship is to leave three unimportant things unsaid each day.

There is a difference between saying it right away and nitpicking. If it’s not important, don’t say it.

Show people that you care before delivering bad feedback.

When you criticize someone without taking even two seconds to show that you care, your guidance feels obnoxiously aggressive to the recipient.

Put the fault within the context of what the person is doing, not the person themself.

A common problem arises when criticizing another person: the fundamental attribution error, which highlights the role of personal traits rather than external causes.

Making a fundamental attribution error is using perceived personality attributes - you’re stupid, lazy, greedy, hypocritical, an asshole - to explain someone else’s behavior rather than considering one’s own behavior and/or the situational factors that were probably the real cause of the other person’s behavior.

It’s easier to say, “You’re sloppy” than to say, “You’ve been working nights and weekends, and it’s starting to take a toll on your ability to catch mistakes in your logic.” But it’s also far less helpful.

Instead of saying, “You’re wrong,” say “I think that’s wrong.”

Balance praise and criticism; but above all, be sincere.

The “shit sandwich” technique might work with less-experienced people, but I’ve found the average child sees through it just as clearly as an executive does.

The notion of a “right” ratio between praise and criticism is dangerous, because it can lead you to say things that are unnatural, insincere, or just plain ridiculous. Patronizing or insincere praise will erode trust and hurt your relationships just as much as overly harsh criticism.

State your good intentions.

“I’m going to describe a problem I see; I may be wrong, and if I am I hope you’ll tell me; if I’m not I hope my bringing it up will help you fix it.”

—

Care personally about your people

Be more than just “professional.” Give a damn, share more than just your work self, and encourage everyone who reports to you to do the same. It’s not enough to care only about people’s ability to perform a job. To have a good relationship, you have to be your whole self and care about each of the people who work for you as a human being.

Acknowledge that we are all people with lives and aspirations that extend beyond those related to our shared work. Find time for real conversations; get to know people at a human level; learn what’s important to people; share with one another what makes us want to get out of bed in the morning and go to work. You need to understand how each person’s job fits into their life goals.

Part of the reason why people fail to care personally is the injunction to “keep it professional.” That phrase denies something essential. We are all human beings, with human feelings, and even at work, we need to be seen as such.

Caring personally is not about memorizing birthdays and names of family members. Nor is it about sharing the sordid details of one’s personal life, or forced chitchat at social events you’d rather not attend.

—

'Radical candor’ also covered many more insightful topics. You’ll find them below in alphabetical order.

Asking for feedback

Stick with the conversation until you have a genuine response.

Embrace the discomfort. Most people will initially respond to your question with something along the lines of “Oh, everything is fine, thank you for asking” and hope that’s the end of the conversation.

It’s essential that you prepare yourself for these scenarios in advance and commit to sticking with the conversation until you have a genuine response.

Example:

Sheryl asked, “What could I have done better?”

He couldn’t think of anything. The presentation had been a home run.

Sheryl wouldn’t let him off the hook though. “I know there was something I could have done better in there.”

He still couldn’t think of anything. Now, he was getting nervous.

“You have a reputation for being great at giving feedback. I bet if you think about it you can come up with something.”

Now, he was sweating. But still she didn’t let him off the hook. She smiled expectantly, and stayed silent.

That was when he finally thought of something, and told her.

“Thank you, I’ll do better next time!”

Building trust

Relationships, not power, drive you forward.

Developing trust is not simply a matter of “do x, y, and z and you have a good relationship.”

It’s a big mistake to assume too much trust too quickly. Don’t pry into deeply personal questions when you barely know a person.

Career design

3 conversations to understand your motivations and ambitions, and take a step in the direction of your dreams:

Note: this is designed as a conversation with your manager, or a coach. You can also use the questions to prompt yourself to think about your life.

Conversation one: life story.

It is designed to learn what motivates the person.

A simple opening: “Starting with kindergarten, tell me about your life.”

Focus on changes that they made and understand why they made those changes. “You dropped out of graduate school after two years to work on Wall Street - please tell me more about that decision.”

The answers enable you to find out motivators:

“I couldn’t even afford orange juice on my grad school stipend, and I just wanted to make more money” → “financial independence” is the motivator

“I was bored with all that theory and no practical, tangible application of the ideas I was working on” → “see tangible results of work” is the motivator

If somebody says they quit running and started playing soccer because they liked being on a team, you might write down “being part of a team” as a motivator.

You’re not looking for definitive answers; you’re just trying to get to know people a little better and understand what they care about.

There may be times when you touch on something that is too personal. If a person signals discomfort at a question, you have to respect that.

Conversation two: dreams

Move from understanding what motivates people to understanding their dreams - what they want to achieve at the apex of their career, how they imagine life at its best to feel.

Bosses usually ask about “long-term goals” or “career aspirations” or “five-year plans” but these phrases tend to elicit a certain type of answer: a “professional” and not entirely human answer.

Giving space for people to talk about dreams allows bosses to help people find opportunities that can move them in the direction of those dreams.

Begin those conversations with, “What do you want the pinnacle of your career to look like?”

Encourage people to come up with three to five dreams for the future. This allows them to include the dream they think you want to hear as well as those that are far closer to their hearts.

Document everything in a document:

Ask each report to create a document with three to five columns; title each with the names of the dreams they described in the last conversation. Then list the skills needed as rows.

Show how important each skill is to each dream, and what their level of competency is in that skill. Generally, it will become very obvious what new skills the person needs to acquire. Now, your job as the boss is to help them think about how they can acquire those skills: what are the projects you can put them on, whom can you introduce them to, what are the options for education?

Make sure that the person’s dreams are aligned with the values they have expressed.

Conversation three: 18-month plan

Get people to begin asking themselves the following questions:

What do I need to learn in order to move in the direction of my dreams?

How should I prioritize the things I need to learn?

Whom can I learn from?

Decision making

Don’t ask people for their recommendations, seek facts instead.

Don’t ask, “What do you think we should do?”

Ask for facts directly.

When you are the decider, it’s really important to go to the source of the facts.

If Steve Jobs was making an important decision and wanted to understand some aspect of it more deeply, he’d go right to the person working on it. There were numerous stories about relatively new, young engineers who’d return from lunch to find Steve waiting in their cube, eager to ask them about a specific detail of their work.

Difficult conversations

Try taking a walk instead of sitting and talking.

When you’re walking, emotions are less on display and less likely to start resonating in a destructive way.

Walking and looking in the same direction often feels more collaborative.

Disagree and commit

A strong leader has the humility to listen, the confidence to challenge, and the wisdom to know when to quit arguing and to get on board.

You often wind up responsible for executing decisions that you disagree with. It can feel like a catch-22:

If you tell your team you do agree with the decisions, you feel like a liar - or at the very least, inauthentic.

If you tell your team that you don’t agree with the decisions, you look weak, insubordinate, or both.

Tell your boss you disagree with a decision, and have a conversation that will help you understand the rationale behind it. And once you understand the rationale more deeply, you can explain it to your team - even if you don’t agree with it.

When they ask, “Why are we doing this, it makes no sense to us, didn’t you argue?” you can reply “I understand your perspective. Yes, I did have an opportunity to argue. Here’s what I said. And here is what I learned about why we are doing what we are doing.”

If they insist on knowing whether you agree, you can tell them in all honesty that your boss listened to your point of view, that you were given an opportunity to challenge the decisions, and that now it’s time to commit to a different course of action than the one you were arguing for.

Hiring

Apple: “We hire people who tell us what to do, not the other way around.”

To keep a team cohesive, you need both rock stars and superstars.

Rock stars are solid as a rock. Think the rock of gibraltar, not Bruce Springsteen. The rock stars love their work. They have found their groove. They don’t want the next job if it will take them away from their craft. Not all artists want to own a gallery; in fact, most don’t. If you honor and reward the rock stars, they’ll become the people you most rely on. If you promote them into roles they don’t want or aren’t suited for, you’ll lose them.

Superstars need to be challenged and given new opportunities to grow constantly.

Most people shift between a steep growth trajectory and a gradual growth trajectory in different phases of their lives and careers, so it’s important not to put a permanent label on people.

The best way to keep superstars happy is to challenge them and make sure they are constantly learning. Give them new opportunities, even when it is sometimes more work than seems feasible for one person to do. Figure out what the next job for them will be.

Make sure you don’t get too dependent on superstars; ask them to teach others on the team to do their job, because they won’t stay in their existing role for long.

Don’t squash or block them. Recognize that you’ll probably be working for them one day, and celebrate that fact.

Performance is not a permanent label.

No person is always an “excellent performer.” They just performed excellently last quarter.

If you’re not dying to hire the person, don’t make an offer.

Even if you are dying to hire somebody, allow yourself to be overruled by the other interviewers who feel strongly the person should not be hired. In general, a bias toward no is useful when hiring.

Idea generation

Be careful not to squish new ideas, they’re often fragile.

While ideas can ultimately be so powerful, they begin as fragile, barely formed thoughts, so easily missed, so easily compromised.

New ideas don’t have to be grandiose plans for the next iPad. Your team may say something like,

“I’m frustrated by this process.”

“I’m not feeling as energized by my work as I was.”

“I think our sales pitch could be stronger.”

“I’d do better work if there were more natural light in the office.”

“What if we just stopped doing X?”

“I’d like to start working on Y.”

Leadership

Bosses provide guidance. It’s often called “feedback.”

Bosses provide team-building. This means figuring out the right people for the right roles: hiring, firing, promoting. Once you’ve got the right people in the right jobs, keep them motivated.

Bosses provide results.

Listening

Loud listening: saying things intended to get a reaction out of people.

To get others to say what they think, you need to say what you think sometimes, too. If you want to be challenged, you need to be willing to challenge.

Expressing strong, some might say, outrageous, positions with others is a good way to get to a better answer, or at least to have a more interesting conversation. “Please poke holes in this idea - I know it may be terrible. So tell me all the reasons we should not do that.”

Steve Jobs would put a strong point of view on the table and insist on a response.

This approach works only when people feel confident enough to rise to the challenge. You need to go to some lengths to build the confidence of those whom you’re making uncomfortable.

Networking

Invite your team and their families or significant others over to your home for a meal. It can be a great way to open yourself up and show you care.

Finding help is better than offering it yourself. More often than not you will have a colleague or acquaintance who can help. All you have to do is to make the introduction and help your direct report structure the conversation.

One-to-one meetings with your boss

Sheryl expected us to come to our 1:1s with a list of problems she could help us resolve. She’d listen, make sure she understood and then she was like a sapper, an explosives expert.

Praise

When giving praise, investigate until you really understand who did what and why it was so great. Be as specific and thorough with praise as with criticism.

Receiving feedback

If a person is bold enough to criticize you, do not critique their criticism.

Listen to and clarify the criticism, but don’t debate it.

Even if somebody criticizes you inappropriately, your job is to listen with the intent to understand and then to reward the candor.

Encourage criticism.

A story from Toyota. Wanting to combat the cultural taboos against criticizing management, Toyota’s leaders painted a big red square on the assembly line floow. New employees had to stand in it at the end of their first week, and they were not allowed to leave until they had criticized at least three things on the line.

Turn feedback into action.

If you agree with the criticism, make a change as soon as possible.

If the necessary change will take time, do something visible to show you’re trying.

Relationship management

Acknowledge emotions and try to master your reactions to other people’s emotions.

Just because somebody is crying or yelling doesn’t mean you’ve done anything wrong; it just means they are upset.

Don’t try to prevent, control, or manage other people’s emotions. Do acknowledge them and react compassionately when emotions run high.

Don’t respond to outbursts or sullen silences by pretending they are not happening. Don’t try to mitigate them by saying things like, “It’s not personal,” or “Let’s be professional.” Instead say, “I can see you’re mad/frustrated/elated/…”

Running meetings

A sample agenda for staff meetings:

Learn: review key metrics (20 min)

What went well that week, and why? What went badly, and why?

Come up with a dashboard of key metrics to review. What are the most important activities and results you see each week that let you know if you are on track to achieving your goals?

Put the dashboard in a place where the whole team can see it. Notes from this conversation should almost always be made public.

Listen: put updates in a shared document (15 min)

Set up a public document where everyone jots down the key things they did last week and what they plan to do next week.

Have everybody take 5 to 7 minutes to write down the three to five things they did that week that others need to know about, and five to seven minutes to read everybody else’s updates. Don’t allow side conversations - require that follow-up questions be handled after the meeting.

Clarify: identify key decisions & debates (30 min)

What are the one or two most important decisions and the single most important debate your team needs to take on that week?

Self-management

Figure out your recipe to stay centered and stick to it.

Prioritize doing it. It’s even more important to focus on making for whatever keeps you centered when you are stressed and busy than when things are relatively calm.

Thoughtful disagreements

Intervene when you start to sense that people are thinking, “I’m going to win this argument,” or “my idea versus your idea,” or “my recommendation versus your recommendation,” or “my team feels…”

Remind people what the goal is” to get to the best answer, as a team.

Have people switch roles.

If a person has been arguing for A, ask them to start arguing for B. If a debate is likely to go on for some time, warn people in advance that you’re going to ask them to switch roles.

Create an obligation to dissent.

If everyone around the table agrees, that’s a red flag. Somebody has to take up the dissenting voice.

Pause for emotion / exhaustion.

There are times when people are just too tired, burnt out, or emotionally charged up to engage in productive debate.

Your job is to intervene and call a time-out. If you don’t, people will make a decision so that they can go home; or worse, a huge fight stemming from raw emotions will break out.

Be clear when the debate will end.

One of the reasons that people find debates stressful or annoying is that often half the room expects a decision at the end of the meeting and the other half wants to keep arguing in a follow-up meeting.

Separate debate and decision meetings.

Don’t grab a decision just because the debate has gotten painful.

Time management

Schedule in some think time, and hold that time sacred. Let people know they cannot ever schedule over it. Get really, seriously angry if they try.

—

And one last quote I found inspiring:

“When the facts change, I change my mind.” - John Maynard Keynes

Click here to browse more book summaries.