When Coffee & Kale Compete by Alan Klement - Book Summary

This is my summary of ‘When Coffee & Kale Compete’ by Alan Klement. My notes are informal and tailored to my own interests at the time of reading. They mostly contain quotes from the book as well as some of my own thoughts. I enjoyed this book and would recommend you read it yourself (check it out on Amazon).

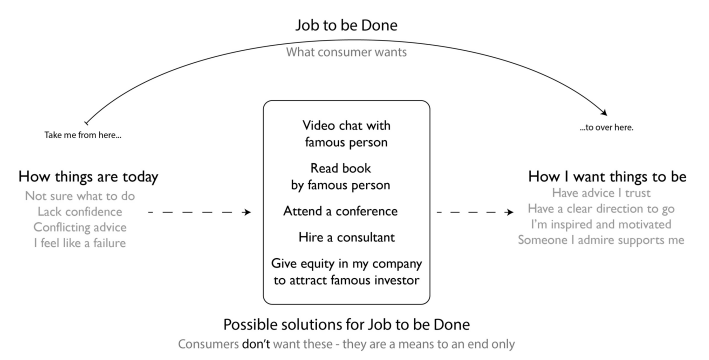

What is a Job to be Done (JTBD)?

Customers don’t want your product or what it does; they want help making themselves better (i.e., they want to transform a life-situation, make progress).

A Job to be Done is the process a consumer goes through whenever she aims to transform her existing life-situation into a preferred one but cannot because constraints are stopping her.

© Alan Klement

—

Principles of JTBD

Customers don’t want your product or what it does; they want help making their lives better (i.e., they want progress). (cf. Badass users by Kathy Sierra)

People have Jobs; things don’t.

Competition is defined in the minds of customers, and they use progress as their criterion.

When customers start using a solution for a JTBD, they stop using something else.

Innovation opportunities exist when customers exhibit compensatory behaviors.

Favor progress over outcomes and goals.

—

How JTBD changes how we think & talk about products

Instead of attaching value to what products are, value should attach to what products do for customers. In other words, stop trying to communicate value with new and improved product features, and start designing more integrated product experiences that are valuable because of what they enable customers to get done in particular contexts of use.

"In the factory, we make cosmetics. In the drugstore, we sell hope." - Charles Revson, founder of Revlon. With these words, Revson marks the difference between what customers buy, and why they buy it.

Jobs-To-Be-Done helps us understand the real jobs customers are using our product for. Not the jobs that we perceive or want them to use our product for.

Very often, innovators think they are studying customers’ needs – when in fact they are studying what customers don’t like about the products they use today, or what customers currently expect from a product.

Jeff Bezos: "Customers are always beautifully, wonderfully dissatisfied, even when they report being happy and business is great. Even when they don’t yet know it, customers want something better, and your desire to delight customers will drive you to invent on their behalf. No customer ever asked Amazon to create the Prime membership program, but it sure turns out they wanted it, and I could give you many such examples."

Example: For many years, manufacturers such as Nokia, Palm, Research in Motion (RIM), and Motorola worked hard to satisfy customers’ stated needs and expectations: make a low-price smartphone with a physical keyboard. Today, those expectations have been reversed. Customers don’t mind shelling out several hundred dollars for a smartphone, and physical keyboards have almost completely disappeared.

Example: In the 1860s, the Pony Express was created to help customers get letters and messages across the United States as fast as possible. It lasted only nineteen months. What happened? Western Union established the transcontinental telegraph. While the Pony Express was trying to solve the “needs” associated with using physical mail, Western Union thought, what if we could communicate without using physical messages?

We can’t build the products of tomorrow when we limit ourselves to the needs and expectations associated with the products of today. Instead, we should focus on what never changes for customers: their desire for progress. When we focus on delivering customers’ progress—instead of what customers say they want—we are free to imagine a world where many needs and expectations are replaced with new ones.

© Alan Klement

—

How to express/communicate a JTBD

Here are some common jobs that have been around for a long time:

Get a package from A to B with confidence, certainty and speed.

Keep everyone up to date on a project they’re involved with.

Get me face to face with my colleague in San Francisco.

There's no "right way" to express jobs to be done. What’s important are (1) does it help you and your team work together? (2) does it describe a “better me” for the customer; and (3) does it help you avoid describing a product or how someone uses it?

When I put people’s JTBD into words, I prefer to keep it simple. I create a statement that combines the forces that generate demand (push and pull) with the Job and when it’s Done. Often use phrases such as give me, help me, make the, take away, free me, or equip me.

It is best to avoid coming up with different types of Jobs or stratifying them. Any attempt to do so will lead to logical inconsistencies and overlaps. It’s best to keep it simple: each Job is a combination of various emotional forces.

The most important test of wording a JTBD is whether it also describes the solution(s) it replaced.

Example 1:

Honest (it's a company) - "(1) free me from the stress I deal with when figuring out what products won’t harm my children, and (2) so I can have more time to enjoy being a parent. (1) is the push / struggle / job; (2) is the pull / how life is better / the job is done.

You can reverse it: “Help me have more time to enjoy being a parent, by taking away the stress I deal with when figuring out what products won’t harm my children.”

You can put it in third person: “Free parents from the stress they deal with when figuring out what products won’t harm their children, so they can have more time to enjoy being parents.”

Example 2:

Clarity, a company's example taken from "When coffee and Kale compete"

From the data Dan has given us, I’d say that the desire for progress is as follows:

More about: getting out of a rut, making a connection with someone whose accomplishments I respect, being inspired, being motivated to act, feeling like I’m on the right path, having confidence in what I’m doing, having success rub off on me, on demand.

Less about: getting expert advice, talking with an expert, giving away equity, having a video chat with a mentor, e-mailing a mentor, mentoring, meeting other entrepreneurs, seeing a mentor live.

Here are some possible descriptions of the one or more Jobs to be Done Clarity is hired for:

Help me get out of an innovation slump with inspirational advice from someone whom I respect.

Give me the motivation to act with a kick in the butt from someone I respect.

Take away the anxiety of making a big decision with assurance from someone else whose has been in a similar position.

These work for me because they don’t describe an activity or task. They describe the motivation that comes before engaging in an activity (i.e., using a solution). Also, notice how these descriptions can be used to describe the other solutions customers had tried in the past (e.g., attending a conference, giving away advisory shares, and using LinkedIn).

—

How JTBD changes how we view competition

Every innovator, whether creating a new innovation or improving an existing one, should have a clear idea of how his or her customers see competition. When you’re creating a new innovation, you need to answer the question, “What are customers going to stop buying when they start buying our solution?” And if you’re creating a new feature for an existing product, you need to ask, “What behaviors or other products is this feature going to replace?”

There's a pitfall in defining markets and competition in terms of product categories vs. seeing markets from a customer's perspective.

Example: Mars came to understand that Snickers and Milky Way, which were thought of as “candy bars, chocolate confections, etc.” were actually hired by customers for very different reasons. The slogan “Milky Way, comfort in every bar” recognized the differences between customers hiring Milky Way to do a “comfort me” Job and the same customers hiring Snickers to do a “satisfy my hunger” Job.

Example: Every day I used to get an espresso from a coffee shop down the street. Two months ago, I bought a Nespresso machine. Now I make my own espressos. The coffee shop has lost my business.

—

The 4 forces that shape customer demand

You need to make sure a true desire for change is taking place and that customers are willing—and able—to pay for a solution. Know the difference between a struggling customer and a merely inconvenienced customer. Don’t look for evidence of just a casual struggle; rather, look for people who were putting a lot of energy into finding a solution.

Consumers don’t simply adopt a product, they switch from something else. When customers start using a solution for a JTBD, they stop using something else. Each time you ‘hire’ a product, you ‘fire’ the incumbent. And, during this period of change, there are four forces that act upon you which influence your decision.

Two forces incline you towards making a change (generating customer demand):

Push: frustration with your current situation, a sense that the ‘as-is’ is sub-optimal, or even downright broken. This triggers the action of looking for something else. People won’t change when they are happy with the way things are. Why would they? People change only when circumstances push them to be unhappy with the way things are.

Pull: when you hear about something else that’s better, you want to check it out. I’m old enough to remember when Google’s search engine was first released. The word of mouth was incredible. People would just tell you ‘This is so much better than anything else’ and you only needed to try it once to jump onboard.

Two incline you against doing so (reducing customer demand):

Inertia / Habit / Attachment: ‘Good enough’ is your biggest enemy. Think of inertia as “a tendency to do nothing or to remain unchanged.” Inertia can manifest in different ways. Mostly, inertia forces are habits.

As Des Traynor, cofounder of Intercom, says, “The popularity of product-first businesses has led to short-sightedness around what’s necessary to create a sustainable business. Some problems persist because they’re quite simply not worth solving.”

The chotuKool case study offers many perfect examples of customers who had good-enough solutions for a JTBD. Rural Indians might like the idea of a small refrigerator, but they were fine using clay pots and shopping for food every day. The chotuKool was a luxury item that didn’t deliver much more progress than their current solutions.

Anxiety: loss aversion, the innate fear of the new.

Anxiety-in-choice. We experience anxiety-in-choice when we don’t know how or if a product can help us get a Job Done. It exists only when we’ve never used a particular product before. It drives away first-time customers. Examples:

“I’ve never taken the bus to work. Is it ever on time? Where do I buy a ticket?”

If I use Clarity, will I sound stupid? Is the call going to be recorded? How is payment handled?

This show seems interesting, but it got bad reviews. Maybe it’s not worth getting tickets for.

How does YourGrocer work? Are there flexible delivery options? Can I get my order today?

Reduce anxiety-in-choice with trials, refunds, and discounts. “Buy one, get one free!” “Lifetime guarantee!” “Free shipping!” “Thirty-day refund!”

Anxiety-in-use. After customers use a product for a JTBD, the anxiety-in-choice largely disappears. Now their concerns are related to anxiety-in-use. For example, “I’ve taken the bus to work several times. But sometimes it’s late, and other times it’s early. I wish I knew its arrival time in advance.” In this case, we know a product can deliver progress, but certain qualities about it make us nervous about using it.

Customers experience some combination of these forces before they buy a product, as they search for and choose a product, when they use a product, and when they use that product to make their lives better.

Advertising/messaging lets you manipulate these four forces. Specifically you can:

Increase the push away: Show how bad their existing product really is.

Increase your product magnetism (pull): Promote how well your product solves their problems.

Decrease the fear and uncertainty of change (anxiety): Assure consumers switching is quick and easy.

Decrease their attachment to the status quo (inertia): Remove consumers’ irrational attachment to their current situation

Studying what customers consider as competition helps you reveal what pushes them to change.

Example: A children’s theater company. To begin, he interviewed parents who had taken their children to the company’s show. He wanted to know why they chose this particular show. Did they consider any other activities for their children besides attending the theater? He told me, “We interviewed a bunch of parents. We learned that the options they had considered [as alternatives to attending the theater] ranged from going to The LEGO Movie and buying the LEGO video game to signing their children up to clubs—like the Girl Scouts.” He talked with these parents about what they did or didn’t like about the other options they had considered. What can the theater do for them that an alternative solution—such as the Girl Scouts—can’t? He also asked these parents about what they did immediately after the shows. Did they have family discussions about them? What were those discussions like? After talking with numerous parents, he began to see a distinct pattern. “We found out that part of the Job these parents are trying to get done—when it comes to entertainment and activities for their kids—was that they wanted help teaching their kids how to be independent…while also reinforcing that they are a member of a team.”

—

Examples of applying JTBD to building products

Example: children's theater company.

Research shows that (1) after the play, parents have family discussions with their kids and (2) the JTBD for parents - "when it comes to entertainment and activities for their kids—was that they wanted help teaching their kids how to be independent…while also reinforcing that they are a member of a team."

Anthony brought these insights to his client. Together, they decided to rewrite parts of the play. They kept most of the content the same, but they added a story arc wherein the hero works with the characters around him to solve a problem. This would give parents a talking point with their children about the importance of working with others.

Bob Moesta:

Bob led marketing and sales at a business that designed, built, and sold homes. The business wanted to offer a home that would appeal to empty nesters—parents who wanted to downsize their home after their children had grown and moved away. Two stated preferences from prospective customers were (1) a smaller dining room because they no longer had big family meals and (2) an expanded second bedroom so their children could visit. Bob’s company delivered on what customers wanted. The result? Tepid sales.

Bob figured out the problem. These empty nesters were willing to change almost everything to accommodate living in a smaller home—except for getting rid of their existing, family-size dining room table. It had tremendous sentimental value because it reminded them of countless family meals. When it came to get rid of it so that they could move into one of Bob’s homes, they couldn’t do it. At a result, many ended up not moving at all.

To fix this, Bob did the opposite of what his customers claimed they wanted: he shrunk the second bedroom and expanded the dining room so that it could accommodate their existing family-size dining room table. Moreover, Bob added a big, old-looking dining room table to the demonstration home, for it would help customers visualize themselves living in this unit. The result? A 23 percent increase in sales.

Companies who asked: what surprising uses have customers invented for existing products?

If you see consumers struggling to get something done by cobbling together work-arounds, pay attention. They’re probably deeply unhappy with the available solutions—and a promising base of new business. When Intuit noticed that small-business owners were using Quicken―designed for individuals—to do accounting for their firms, it realized small firms represented a major new market.

Recently, some of the biggest successes in consumer packaged goods have resulted from a job identified through unusual uses of established products. For example, NyQuil had been sold for decades as a cold remedy, but it turned out that some consumers were knocking back a couple of spoonfuls to help them sleep, even when they weren’t sick. Hence, ZzzQuil was born, offering consumers the good night’s rest they wanted without the other active ingredients they didn’t need.

Click here to browse more book summaries.